A peculiarity of the North-East of England — a region which consists primarily of run-down, greying towns that are wind-weathered and hemmed in by the cold North Sea — is that many of the place names are soft and warm and beautiful. Osmotherley, Darlington, Roseberry Topping. Hartlepool. I always say, if you didn’t know anything about Hartlepool, you would hear the name and simply think: how nice. A pool of hearts.

Something like this, in fact, happened to photographer Jamie Hawkesworth during the thirteen-year long project, began in 2007, in which he travelled around Britain taking photographs of whatever caught his eye. One day he stood in front of the board at St Pancras Station, watching the lists of departing trains flicker on the screen. ‘Hartlepool’, that lovely word, got his attention. Soon he was aboard the Grand Central Rail train, and three hours later he found himself in Hartlepool. He was astounded by what he found there. A matter of hours ago he hadn’t known the place existed, and now he was standing with his face to the ocean, observing the way the abandoned factories oozed into the sea. ‘I had never seen anything like that in my life,’ he would later recall. ‘I remember walking around thinking, I can’t believe this exists.’ Later, wandering through a neighbourhood, he found two shirtless boys, one with his arm bandaged, flipping themselves off a stack of mattresses they had dragged to the patch of grass in front of their house. Once again, he struggled to believe what he was seeing, these picture-perfect moments delivered to him from such an unlikely corner of the country.

I was born in Hartlepool, this strange town of boy-flippers and deserted plans. When, at 18, I left to go to university, I lived for the first time amongst people who, like Hawkesworth, had never heard of it in their lives. There are several little stories I like to tell about the town to such strangers. One of my Hartlepool-stories goes like this: if you’ve heard of it, it’s most likely for the wrong reasons. When I was growing up, the town boasted the country’s highest rate of teen pregnancy, one of the highest rates of unemployment, and the Teeside population (of which Hartlepool is a part) was credited with bringing back syphilis, a centuries-defunct STI. Hawkesworth, though, was intent on photographing unglamorous UK destinations in a favourable light, even if they were ‘very hard places, not in the sense that someone’s gonna be killed […] but in being very cold and the light very dull. When I came to the dark room to print them, I always wanted everything to have quite an optimism and… like a celebration. So I felt that if I printed stuff on the warmer side, with, you know, a bit more yellow or whatever, it would bring optimism.’

I too have my own ways of warming up the picture. Many of my Hartlepool-stories are whimsical, as if to counteract the negative impression my listener may already have of the town. Did you know, I say to a bored Londoner who only asked where I’m from out of politeness, that from the McDonalds window in Hartlepool you have a view of the HMS Trincomalee, the oldest war ship still afloat in the world. Or that Hartlepudlians are sometimes pejoratively called ‘monkey-hangers’ because of a centuries-old legend in which the French navy shipwrecked on Hartlepool’s shore, and the only living passenger in the wreckage was a monkey dressed in soldier’s uniform. So the townspeople, having never seen a French person before and assuming this must be what they looked like, hanged the monkey.

Which is a little bit chilling, so then I correct course by saying: the mascot for Hartlepool FC, the town’s football team, is, perversely, a monkey. Called (here, if you are the storyteller, it’s best to pause for both dramatic and humorous effect) H’Angus. In 2002, Stuart Drummond, the mascot at the time, who had no political experience whatsoever, ran for Mayor — and won. (The town’s two-fingers to the politicians who kept trying to win them over, only to forget about local interests upon victory.) He was the first and only directly elected Mayor in Hartlepool’s history, and was reelected not once, but twice. A guy in a monkey costume. I sometimes meet people who, when I ask them about where they grew up, shrug their shoulders in complete indifference, because they are from villages which they feel are nondescript and vibeless. It is impossible to feel indifferently towards your hometown if your hometown is Hartlepool.

Hawkesworth’s rose tinted lens was flattering, but he himself denies that his photographs, borne of fleeting encounters and devoid of political ‘agenda’, could possibly ‘sum up that place’. Neither am I presenting the whole picture when I feed new friends these morsels of my eccentric hometown filled, by my telling, exclusively with residents funnier and friendlier than anyone born south of Sheffield. Then, over the summer, as I sat in an office in London, someone sent me another Hartlepool-related tale. This one was from a major news outlet, and the headline blared something awful: ‘Thugs set fire to cop cars & hurl rocks in Hartlepool’. Oh, I thought. That old story.

Chris Killip was good at telling the stories of North East towns. Having spent enough summers selling tourists photographs of themselves on the beach, and plenty of nights working in his parents’ pub, he had left his own hometown in the Isle of Man, and settled himself and his camera equipment in the North East. It was the 1970s, and whilst he had a vague sense that it was important he documented the local communities and the industries — seacoaling, mining, steelworking — in which their lives were inextricably intertwined, he was not yet cognisant that he was recording a way of life that was about to be set ablaze by deindustrialisation and Thatcherism.

Startling, intimate photographs of a tough, struggling region emerged from the film slotted into Killip’s camera: a young boy sitting on a brick wall, his knees to his chest and his eyes screwed shut; three girls playing out, the road covered in their chalk-scribbles, a small brick wall separating them from the colossal ship which towers over them, with the words ‘TYNE PRIDE’ painted on its side. No details, whether rough, dirty, or hopeless, are skipped: crumbling brick, peeling paint, splatters on the bus stop, the words graffitied on a brick wall: ‘DON’T VOTE. PREPARE FOR REVOLUTION.’

Killip was adamant that photographers had a responsibility to the communities that they captured (later in life, as a Professor of Photography at Harvard, he would ask his disconcerted students if they had ever visited their subjects’ homes without their cameras). His stint in the North East was not a lighthearted rendezvous; he became involved and invested in the communities there, a well-known face and well-liked person. He was indignant on behalf of the people who had welcomed him into their towns, and adamant that he would tell their already half-forgotten story. When he eventually published a book of his photographs taken in the region, In Flagrante (1988), it was accompanied by the indignant declaration: ‘The objective history of England doesn’t amount to much if you don’t believe in it, and I don’t, and I don’t believe that anyone in these photographs does either as they face the reality of de-industrialization in a system which regards their lives as disposable.’

Killip’s righteous anger was warranted; he had watched the communities he loved disintegrate before his eyes. By the end of the 80s, the housing estates he was photographing at the beginning of the decade were being torn down, and the men who he had photographed toiling at sea and on shore found that their jobs had become obsolete.

There were other calamities. It had taken time for the people of Skinningrove, a tight-knit fishing community in North Yorkshire, to accept Killip’s presence. The first residents whose trust he gained were a handful of young men who went out in boats to check the lobster pots. In his photographs of the group, they recline on the shoreline, smoking tabs, climbing out of boats. It is obvious from the position of Killip’s camera that he is one of the gang. (The photos bring to mind a strange memory: in school, me and my friends used to laugh so constantly and hysterically at lunchtime that once the Deputy Headteacher walked past us, cackling as was our wont, and said, in an almost injured tone, ‘Girls. Always laughing.’)

In 1986, however, tragedy struck: the boys’ boat capsized, and two of the young men drowned. Leso, a charismatic lad who had helped Killip settle into Skinningrove and convinced several of the residents to have their photograph taken by him, died, along with his friend David. By now a well-known figure, Killip was asked by one of the boy’s mothers for any photos he had of her son. He gave her the three dozen or so pictures he had taken of him from the ages of thirteen to seventeen, and after doing the same for the other boy’s parents, left the town for good.

Maybe Hawkesworth was onto something: his photographs are golden and hopeful because they are completely unburdened by any real knowledge of the place. Killip, on the other hand, insisted on knowing. This led to some of the most significant photography of Britain since the Second World War, but also meant that he witnessed, and experienced, profound and tragic loss. Surely there is always the danger that, the closer you get, the more painful it will be to look. Killip refused for more than four decades to publish the photographs he had taken in Skinningrove.1 I know Hartlepool better than any place in the world, but I always struggle to tell the whole truth about it.

In some ways, I feel the period Killip captured, one which was so fraught and so pivotal for the North East, doesn’t belong to me at all; my ancestors were not on ships off the northern coast of England but were, in the decades following the partition of India, building lives in the newly-invented Pakistan.

Then again, 1970 was the year my grandparents moved to Hartlepool (after a brief stint in North Shields). The Urdu word for ‘moving [from one place to another]’ is ‘shift’; the shift, in both the English and Urdu sense of the word, that my grandparents undertook by relocating to England was seismic. It is impossible for me to understand what it must have been like for them; Hartlepool is too familiar to me for me to imagine it through the eyes of a young couple with a new baby, arriving from a small town in Pakistan. How strange the baltic, stark landscape of the North East must have seemed to them, how odd it must have been to be suddenly surrounded by English people who eyed them with suspicion or confusion. My grandmother had a Masters in English Literature, and no doubt my grandfather, too, had heard recordings of English being spoken in RP, BBC-approved tones; to then be told that the incomprehensible language they were hearing — where all the vowels sounded as though they had been scooped out with a spoon, where half the consonants in a word could be abandoned, and a heavy helping of regionally-specific vocabulary had been thrown in — was, in fact, English, must have been shocking.

It was in 1970 that my Aunty P, a nurse working the night shift at Hartlepool hospital, peered over the balcony of her floor and watched the young Pakistani doctor and his wife, with their baby in a pram, leave their flat at the hospital and go for an evening stroll together. She often found herself looking out for them on her night shifts after that; come Christmastime, she made a plan to introduce herself. She knocked on their door, bearing Christmas presents, and the doctor’s wife, my grandmother, delightedly invited her in. This was the first and firmest friend that my grandmother would make in Hartlepool, because of Aunty P’s inquisitive kindness and my grandmother’s warmth and generosity; they would remain like that, chatting and sipping tea in the living room, until my grandmother’s death in 1995. (My Aunty P remains a firm fixture of our family life; she was present at my birth, and when I go to Hartlepool now it’s her house that I stay at.)

Eventually my grandmother worked up the nerve to start making friends herself, in this baffling, freezing England. Once she started, in fact, she found she couldn’t stop: she befriended women she met in the queue at the post office, in the Textiles class she took at the local college, and women who were the wives of her husband’s colleagues. She invited them over and cooked for them, entreated them to tell her jokes and stories, and enthusiastically told them about her life in Pakistan, and about Islam. My grandmother was in love with Islam, and with being Muslim. So lonely in this new land, with no one around who looked or spoke like her and her family, she was desperate to communicate this faith which shaped her entire world. And the friends she made in Hartlepool liked her (they still, when I see them, tell me how much they liked her), and liked hearing her talk about Islam; some even converted to the religion. By the time of her death, my mother and her siblings, none of them older than 25, were inundated at her funeral by bawling locals, bearing on them and expressing their feeling that they, themselves, had lost their own sister, their own mother.

Many of the people who know about Hartlepool, though, know a very different story than my grandmother’s, one which is not about love and community, but about hatred and fear. I must also tell you this story, though I’ve been putting it off relentlessly, and mustn’t hide from you that Hartlepool is a bruise that people — grifting politicians and radicalisers, for example — keep poking, in the hope that it still hurts. The deindustrialisation which Killip railed against also impacted Hartlepool, leaving the primarily working-class population in a state of aimlessness from which it has still not recovered. In the last decade or so, the possibility of the town electing a far-right MP has seemed an increasingly likely one (an outcome far less attractive than a Mayor in a monkey costume). In 2016, 70% of the town voted for Brexit. In 2019 Brexit Party and Conservative Party members took over the local council. In spite of the fact that Hartlepool has the lowest rate of immigration in the North East (and the North East’s foreign-born population is around 6%, less than half of the country’s national average), and almost 97% of the town’s population are White, the popularity of both Brexit and right-wing political candidates was based on the staunchly anti-immigrant rhetoric with which they ran their campaigns. For its ills — amongst which are some of the highest unemployment rates in the UK, and the lowest life expectancy in the country — it seems Hartlepool has found a simple cure: sending its brown and black people packing.

Over the summer, an earnest attempt was made to do just that. After the murder of three little girls in Stockport, rumour spread that the killer was a Muslim immigrant. The rumours were false, but no matter; violence spread, first in Stockport and then throughout northern England, like blood seeping from a reopened wound. Hartlepool was the second location where riots took over: hoards of locals gathered and headed for the mosque, with the aim of destruction and the garbled intention of retribution. Police stopped them before they could reach the mosque, so they contented themselves by tearing up a street of shops, chanting racist slogans, and punching brown passersby in the face; their own town coming apart in their hands.

The next day a Gofundme was set up for the mosque by a concerned Hartlepudlian, to which locals donated thousands of pounds (the mosque, in turn, gave the money back to local charities). Which is a nice story, and a true one. But all of these stories are true, including the ones I have about the innumerable occasions of discomfort and pain that I experienced growing up as Muslim girl in the town. Any story I try to tell about Hartlepool contradicts and defies another one. So how on earth does one try to tell the story of a place?

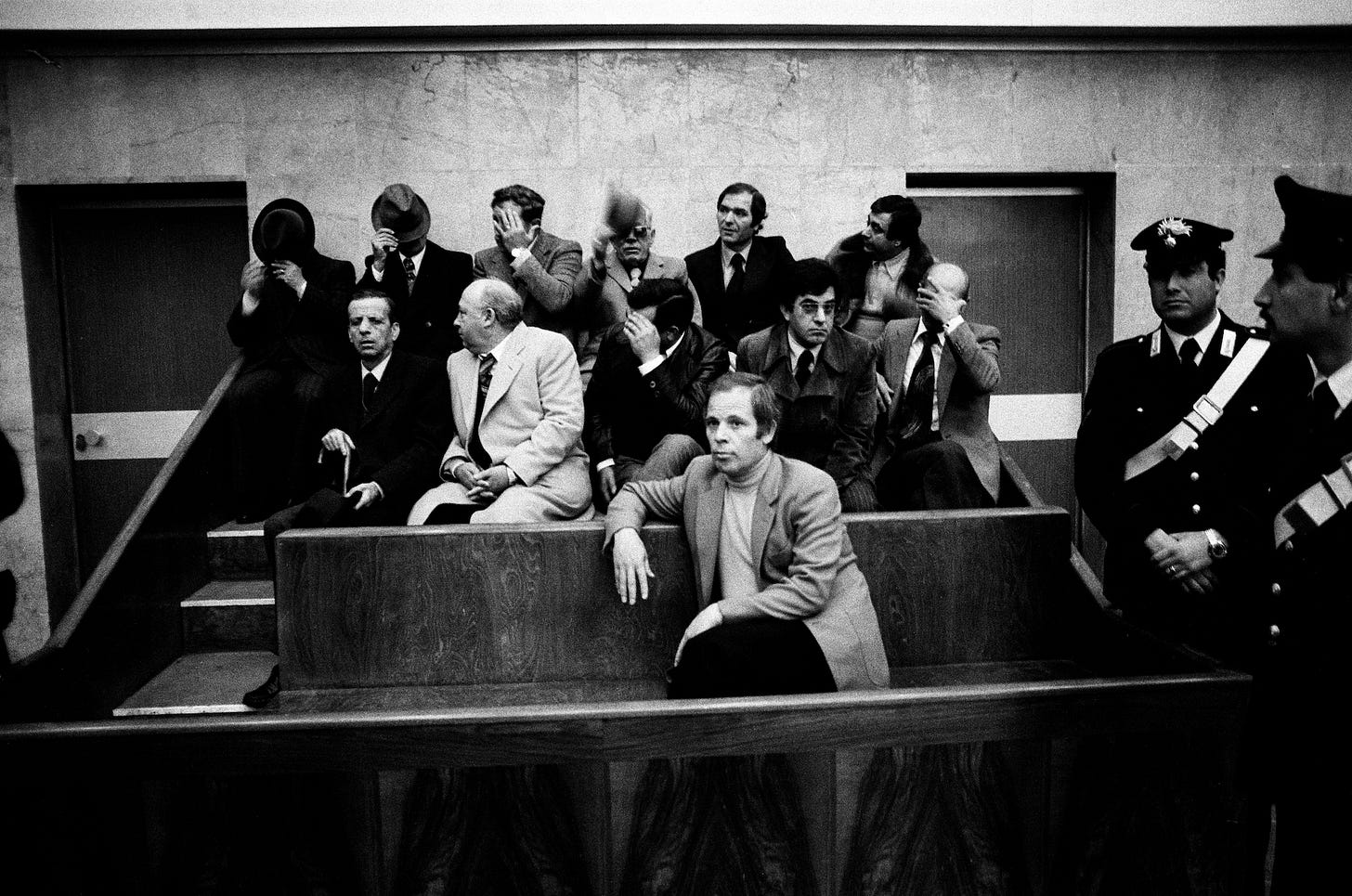

Letizia Battaglia was born in Palermo, Sicily. After her divorce from her husband in 1971, she had taken her three daughters to Milan, only to return a few years later. A war between Mafia clans had broken out in and around Palermo, and the city was wracked by horrific violence and gripped with fear. At some point, during her work for the left-wing paper L’Ora, she picked up a camera and snapped some photos. Her desire to write was extinguished instantaneously, and for the next two gory decades she was the leading photojournalist to document the Mafia’s brutal cruelty that was destroying the city. Her stark, chilling photos became renowned, and she was put on a wanted list: a letter arrived to her house in which the Mafia demanded that she ‘leave Palermo immediately … With your way of doing things you have broken our balls too much’.

Many of Battaglia’s photographs are painful to look at: the Mafia’s victims sit in cars, dead, bullet holes visible and blood pouring out of their mouths. Freshly-widowed women crouch, bereft, beside the corpses of their husbands, gunned down in the streets of Palermo. Battaglia, at immense personal risk, also took photographs of Mafia members whenever she could. Even her pictures of more personal scenes — couples intertwined on the beach, or a young girl playing out, holding a football — are charged with despair. In one, a young woman dances at a New Year’s ball, but what could have been a snapshot of exuberant youth is instead deeply troubled; the background figures are blurred, and the girl in the foreground is caught in a jerking motion, as if desperately trying to break free. Even in moments of intimacy or repose, Battaglia’s work seems to say, the locals are haunted by the danger that has enveloped their town.

Battaglia’s camera took in all of Palermo. That this was her hometown did not charge her photographs with sentimentality; there was nothing she tried to cover up. She captured scenes of love and of brutality, of ordinary daily activities and of extraordinary violence and loss. In 1985, Battaglia was elected to the Palermo city council, and was later appointed regional deputy in the Sicilian government. She ran photography and arts magazines in her hometown, and helped to rebuild the historic town centre that the Mafia had almost destroyed. She kept documenting the destruction there, telling the story of her shattered city — even after two of her close friends were killed by the Mafia and the grief threatened to propel her out of the place forever. Her honest, bloody images were an act of resistance, as well as a way of encouraging the people of her hometown to resist with her: come on, her photographs seem to say, look at what they are doing to us.

In the weeks after the riots in England this summer, people rushed to find a reason for the outbreak of violence: they credited an increase in radicalisation due to fractured communities and online conspiracy theorists, and a racist and colonialist past which has been evaded for too long. All of these stories are, I think, true — the tricky thing is, is I can’t be bothered to tell them. Instead, I want to tell you my own misleading, contradicting tales. I want to tell you a garbled legend of a town called Hartlepool, a place rife with aimlessness and disappointment, where ancient warships are afloat but unusable, and monkeys are either subject to public execution or allowed to attain the highest position of authority in the land. Girls of the town guffaw over their food, whilst the young men plot acts of pointless violence. The population is aging and dwindling, a problem which could be solved by an influx of immigrants who would restore activity to the area and generate income. Alas, the inhabitants continually treat strangers and brown-skinned residents with distrust, as a result of a curse put upon their ancestors’ when they wickedly hanged what was almost a French soldier. Dilapidated factories stretch out as far as the eye can see, spilling into the ocean, a remnant from a time before the people were expelled from the water. The sea, once a great ally, is now a dead end.

I left Hartlepool three years ago, along with the last remaining members of my family who lived in the town. From Battaglia we learn that there is a way to tell the story of a place, but it requires brutal honesty, an unflinching eye, and a storyteller who is willing to stick around. On all three counts, I am unqualified.

Just before the end of his life, Killip would relent, publishing a handful of the photographs he had taken there for the first time. Decades after leaving Skinningrove, he would return, to post copies of the photos through the letterbox of every house in the village.