In one of the photographs at ‘Dennis Morris: Music + Life’, a retrospective of Morris’s work showing at the Photographer’s Gallery until the 28th September, a young boy presses a Union Jack flag, much bigger than his own body, against himself. In the middle of the flag is a portrait of Queen Elizabeth II; the words ‘God Save the Queen’ cover her eyes and ‘Sex Pistols’ obscure her mouth. It is not a flag after all, but artwork associated with the Sex Pistols debut album, Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols, released in 1977.

When Morris reaches the photograph, displayed amongst a collection of his photos of the punk subculture in ‘70s London, he chuckles. On the day he took that photo, the release-day of the Pistols’ controversial album, he had assumed the young boy’s father had brought him to the record shop to buy it. He would encounter the same boy years later, now grown up and living in LA, who would tell him the truth: that it was his uncle who had been babysitting him that day and, despite strict instructions to do the opposite, took him to buy the album. When Morris’s photo of the boy ended up in the papers, his mother was furious, and she never spoke to her brother again. ‘That was the power of punk at the time,’ says Morris, ‘it tore families apart.’

This was England, then, in the 1970s: a declining economy, staggering levels of unemployment and incessant strikes had resulted in a population that was angry, disillusioned and willing to chew up the established order if it meant it might spit out something new. Both parts of the retrospective — the first displaying his iconic portraits of reggae, rock ‘n roll and punk icons and the second his street photography of black, white and South Asian working class communities in England — bear testament to Morris’s impressive ability to have identified, early on, the people and moments that would come to define this turbulent and significant period of British history.

Part of the Windrush generation, Morris emigrated from Jamaica to England with his mother in early childhood. He grew up in a single bedroom in Hackney, divided into a bedroom and living room by a curtain, and earned the moniker ‘Mad Dennis’ from his peers due to his fascination with photography and his insistence on keeping his camera on him at all times. In 1973, aged just 14, he skipped a day of school to wait outside of London’s Speakeasy Club, hoping to encounter Bob Marley and take his picture. After a few hours Marley materialised and, charmed by Morris’s youth, or his precociousness, or the novelty of his Cockney accent, agreed to have his photo taken; by the end of the day, a friendship had blossomed, and Marley invited Morris to join him on tour.

This would be the beginning of a relationship that lasted until Marley’s untimely death in 1981, and a significant portion of the retrospective is dedicated to Morris’s portraits of Marley. The intimacy and stillness of these photos — Marley smiling, Marley smoking, Marley looking young and solemn, contemplating a football he has balanced in his fingers — speak to Morris’s unprecedented access to the musician. Many of the photos were taken in the early years of Marley’s career, before the now larger-than-life icon achieved worldwide fame, and as his celebrity increased Morris’s photos came to grace the covers of NME and Time Out, helping to establish his place in the music industry.

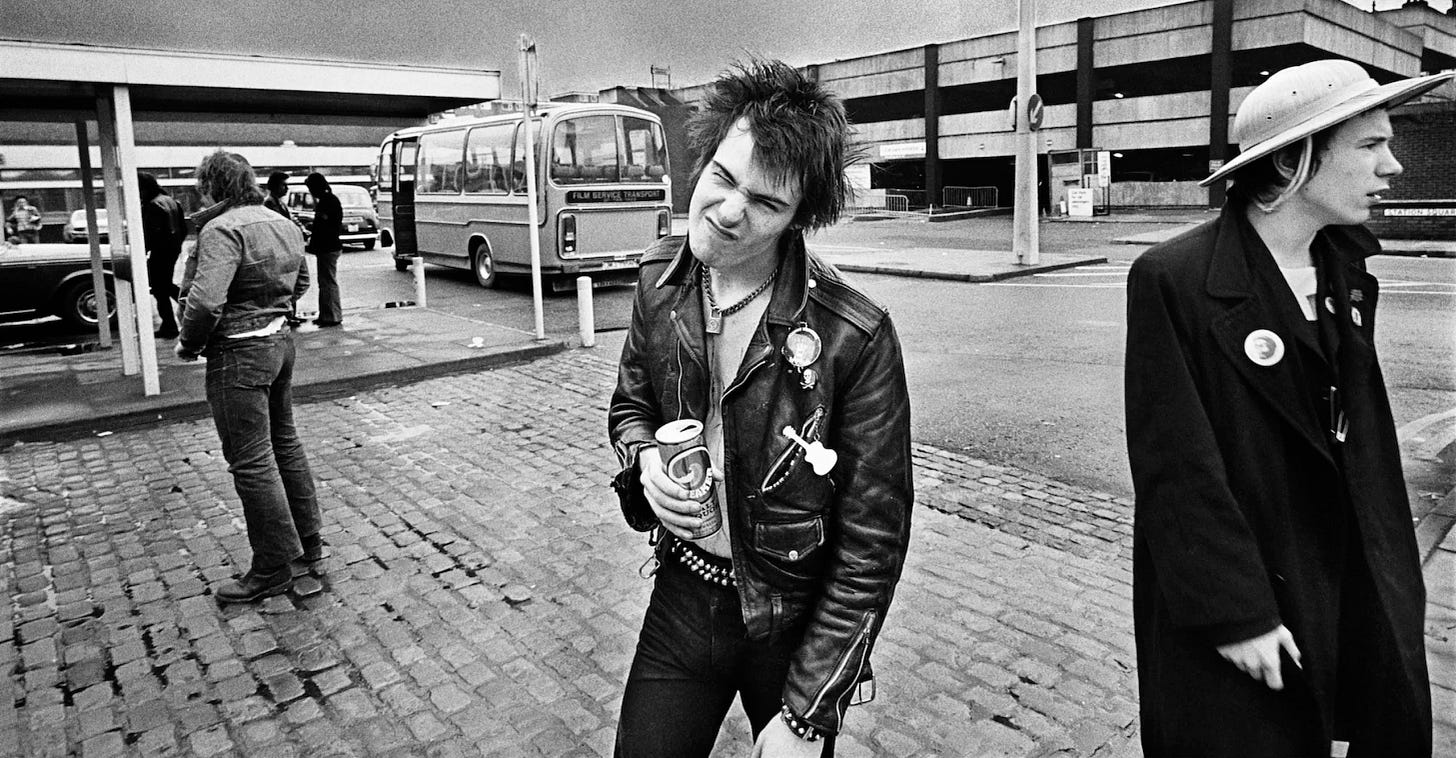

It was his portraits of reggae icons, in fact, that caught the eye of John Lydon, aka Johnny Rotten, who asked Morris to take photos of himself and his newly-formed band the Sex Pistols. Morris describes his work as the Sex Pistols’ tour photographer as his ‘war photography’, recounting gigs in which he pushed through to ‘the frontlines’ of the crowd with his hood up (‘to avoid the spit’), and attempted to get a steady shot as the writhing, frantic bodies around him threw him up into the air.

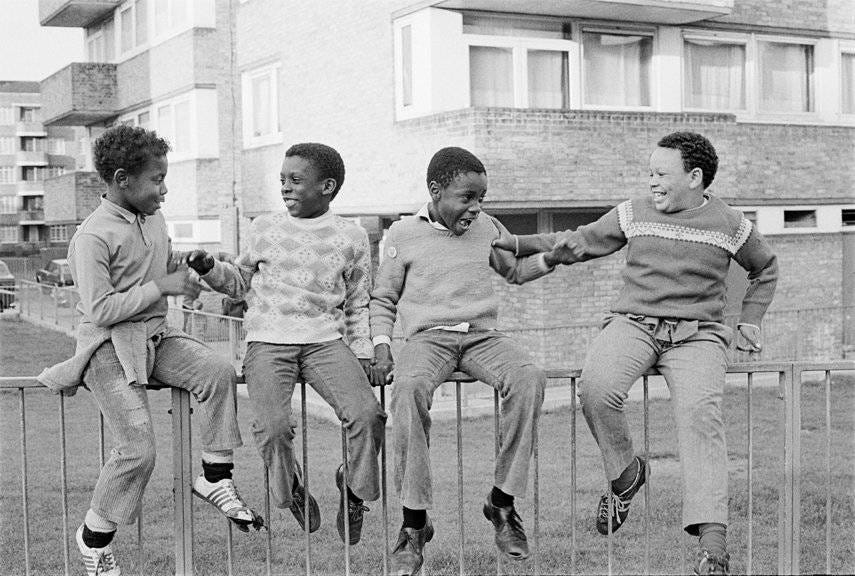

His instinct for what was making Britain tick extended beyond musicians and into the streets, where immigrant communities were beginning to establish themselves in the country. Growing Up Black depicts the daily life of the Black community in his own neighbourhood in Hackney, whether sitting in bedrooms or pouring out of church. The images communicate the struggle demanded of people intent on forging a life in a new country, in cramped and difficult conditions, while maintaining hope and self-respect throughout: ‘our rooms were spotless, everything in its place,’ notes Morris, ‘although times were rough, we were always dignified.’ This is clear in the photos: one sharply dressed gentleman stands proudly before lines of washing which contour the small room in which he stands. In another, a group of smartly-dressed boys balance on a fence and giggle together.

Morris’s curiosity took him further afield, to the growing South Asian community in Southall. His pictures there captured intimate, everyday moments: men gathered in crisp white turbans, confetti being poured over a smiling bride, a group of brown and white teenaged friends smiling giddily at the camera. In This Happy Breed, another series of photos, Morris captured communities living in predominantly white working class towns around England. Humour and resilience radiate from people at strikes, gurning contests and pensioners’ clubs alike. When I ask him what drew him to the white working class communities of England, he shrugs, ‘I grew up surrounded by them.’ (After all, he knew the Sex Pistols because they grew up around the corner from each other: ‘They were the white kids we used to see at the blues dances.’) Politically-motivated narratives often draw sharp distinctions between the white and black or brown working classes, as though one is able to lay the blame for their own oppression at the other’s doorstep. In Morris’s work, however, their struggles and concerns are obviously connected.

When I ask how he was able to integrate himself into all these different circles, he gives the impression that they were mostly unbothered by his presence. In fact, they welcomed him in, as both photographer and subject were curious to learn more about one another, and willing to have their preconceived notions disproved. ‘You know,’ he tells me, ‘when you’re open, people open themselves to you. I knocked on doors and they welcomed me in.’

Ooh I’ll have to catch this while it’s on so I too can experience the power of 70s punk